Chuck Peddle: Personal Computer Pioneer, Dies At 82

Charles “Chuck†Peddle, a visionary electrical engineer who played a prominent role in the early years of the personal computer revolution, died on December 15 after battling pancreatic cancer. He was 82.

Chuck joined Motorola in 1973. He was brought to help out with Motorola’s latest project – the 6800-series microprocessors. The chip was complex, physically large, and therefore expensive. Chuck saw the problem and wanted to pursue a lower-cost simpler variant that would attract more customers and be more accessible. The price point he was going for was $25 or 1/12th that of the original 6800. Motorola was not impressed by this idea and in 1974 Chuck was formally told to stop working on the project. Frustrated with management that failed to see his vision, in 1974 shortly after the launch of the 6800, Chuck, along with a small group of chip designers, left for a then-largely-unknown company: MOS Technology. MOS was founded just five years earlier for the sole purpose of second-sourcing designs from other companies. In 1974 things drastically changed – with the new design team joining on board – the simple second-source fab became a design house. The team’s first project was to build a new ground-up microprocessor.

In just a year – with the hindsight gained from their Motorola days – the team, headed by Peddle, designed a series of microprocessors. Many stories were told about that time at MOS. Perhaps the most interesting one is that of the 6501 MPU. The 6501 was designed to be socket compatible with the 6800, albeit it was not software compatible since the instruction set (and thus the hardware and registers) were different. One could, in theory, replace the 6800 chip in an existing system with a MOS 6501 and get it to work. The 6501 was never really meant to be mass-produced and Chuck himself was often quoted as saying it was an “in your face” to Motorola. The 6501 samples were sold for a mere $20.

The real revolution came with the 6502. With the exception of being pin-incompatible, the difference between the two was minor. The real magic was in its performance and cost. Chuck had a hard limit on the die size of the chip and placed constraints on the architecture in order to get to the magic $25 price point. The plan worked and when the chip was ready for market, not only was it much cheaper than competing Motorola and Intel processors, due to its hardware simplifications, the chip was also much faster.

In an effort to get more developers to try out their processors, MOS designed and sold a number of complete reference designs based on the 6502 including the Keyboard Input Monitor (KIM), the Teletype Input Machine (TIM), and the Microcomputer Development Terminal (MDT). Those machines can be considered one of the world’s first single-board computers (SBCs). The KIM-1 was a success. Not only did it attract the engineers they wanted, but it was also widely popular by the hobbyist community. Other companies, such as Rockwell and it’s AIM-65 computer, that developed their own development computers based on the KIM-1, have enjoyed similar success.

Concurrently with everything else, by 1975, Commodore became MOS largest customer. But Commodore wasn’t buying the 6502 chips, they were buying second-sourced TI chips. With the collapse of the calculator market, TI started vertically integrating, building its own calculators. At the same time, TI also raised the price of its chipsets – often exceeding that of their own calculators. By 1976, the move resulted in TI severely undercutting Commodore and nearly bankrupting them. TI’s move cascaded all the way to MOS which was thrown into a financial crisis. In a last-moment injection of capital and convinced vertical integration was the only way to survive, Commodore started acquiring its own supply chain companies. Among those companies was MOS Technology.

At Commodore, Chuck pitched his personal computer vision to Commodore founder Jack Tramiel, convincing him that calculators are a dead-end. In late 1976, Tramiel gave his personal approval for the project and the Commodore Personal Electronic Transactor (PET) was born. The machine was to be ready by the 1977 Consumer Electronics Show. In the same year, Chuck was also tasked with pitching and marketing the 6502 to various companies. In Brian Bagnall’s book, it was revealed: “While we were out visiting Atari, my westcoast [sales] manager [Petr Sehnal] said, ‘Hey, there’s some kids working on a machine in his garage and it’s not working. We have a development system with us, so why don’t we go over and help them?'”. The two young men who visited Chuck in his hotel suite were Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs.

The PET started shipping in the months prior to its introduction in January 1977 and its early success resulted in a back-log of over half a year. The PET saw moderate success and paved the way to the Commodore VIC-20, a more economical personal computer that sold for less than half the price. A year later Commodore introduced the Commodore 64, the company’s most successful personal computer. This computer was based on the MOS 6510, an enhanced version of the original 6502. The Commodore 64 went on to sell 10s of millions of units.

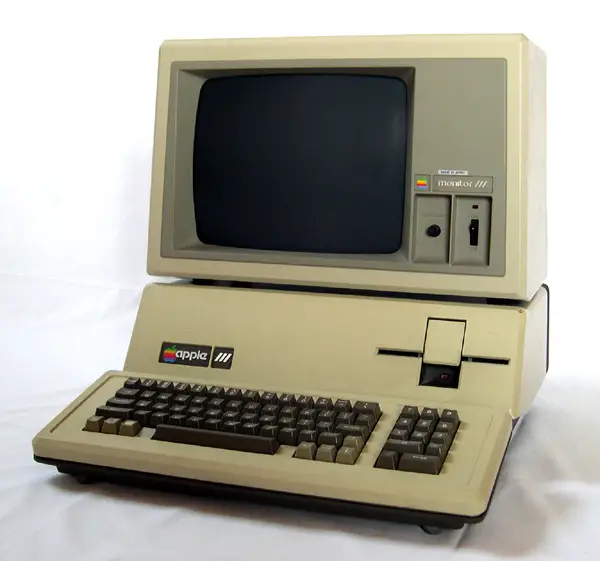

Beyond Commodore’s own computers, the 6502 (and its later variants) saw enormous success, powering computers such as the Apple I, Apple II, Apple II Plus, Apple IIe, Acorn Atom, BBC Micro, Atari 400, Atari 800, Atari 2600, and dozens of other. Beyond personal computers, the 6502 found its way to billions of other devices including toys such as the Tamagotchi and the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES).

Peddle is survived by his partner of 35 years, Kathleen Shaeffer, three brothers and a sister, and his six children, Debbie, Diana, Cheryl, Thomas, Vernon, and Robert. His family has stated a memorial service is planned for early 2020 in Santa Cruz, CA. The details have yet to be determined.

–

Spotted an error? Help us fix it! Simply select the problematic text and press Ctrl+Enter to notify us.

–